By Paul Homewood

h/t Jonathan Scott

Another day, another BBC propaganda piece!

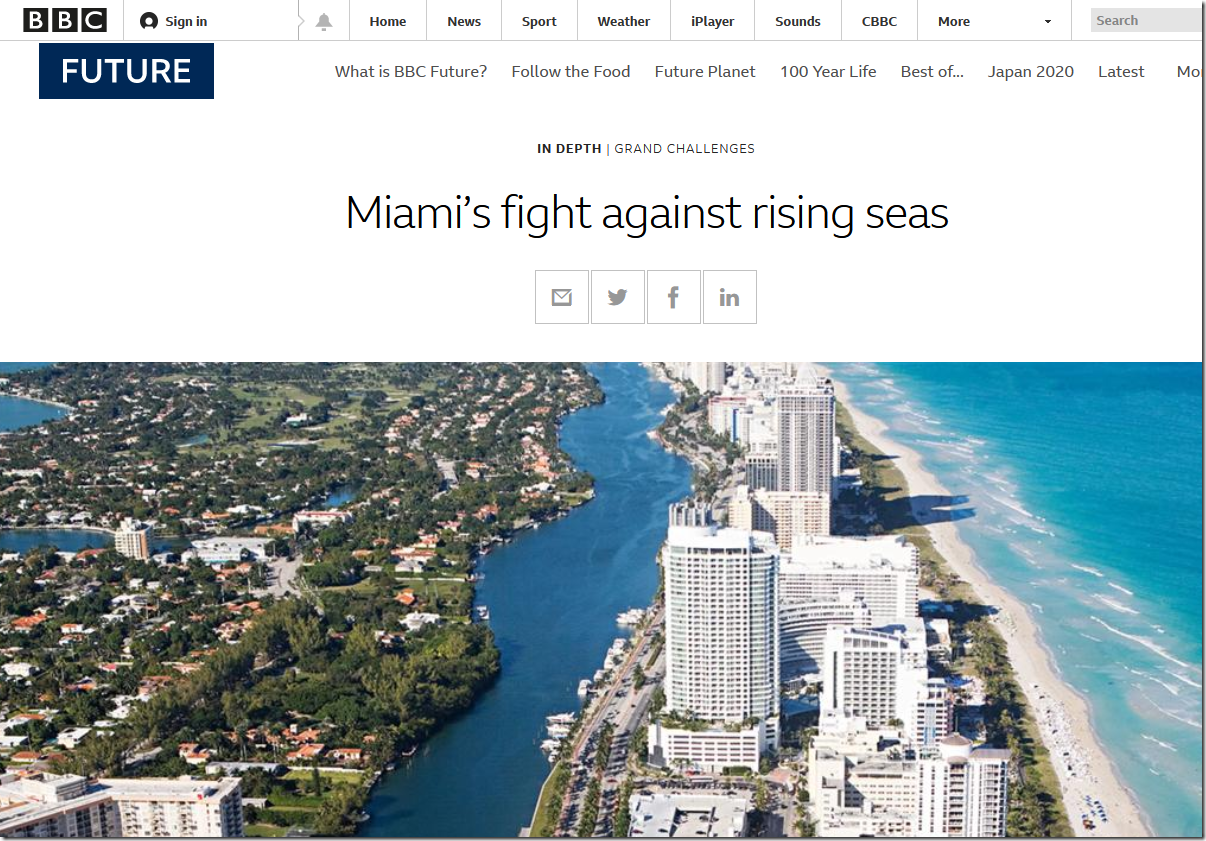

Just down the coast from Donald Trump’s weekend retreat, the residents and businesses of south Florida are experiencing regular episodes of water in the streets. In the battle against rising seas, the region – which has more to lose than almost anywhere else in the world – is becoming ground zero.

The first time my father’s basement flooded, it was shortly after he moved in. The building was an ocean-front high-rise in a small city north of Miami called Sunny Isles Beach. The marble lobby had a waterfall that never stopped running; crisp-shirted valets parked your car for you. For the residents who lived in the more lavish flats, these cars were often BMWs and Mercedes. But no matter their value, the cars all wound up in the same place: the basement.

When I called, I’d ask my dad how the building was doing. “The basement flooded again a couple weeks ago,” he’d sometimes say. Or: “It’s getting worse.” It’s not only his building: he’s also driven through a foot of water on a main road a couple of towns over and is used to tiptoeing around pools in the local supermarket’s car park.

Ask nearly anyone in the Miami area about flooding and they’ll have an anecdote to share. Many will also tell you that it’s happening more and more frequently. The data backs them up.

It’s easy to think that the only communities suffering from sea level rise are far-flung and remote. And while places like the Solomon Islands and Kiribati are indeed facing particularly dramatic challenges, they aren’t the only ones being forced to grapple with the issue. Sea levels are rising around the world, and in the US, south Florida is ground zero – as much for the adaptation strategies it is attempting as for the risk that it bears.

One reason is that water levels here are rising especially quickly. The most frequently-used range of estimates puts the likely range between 15-25cm (6-10in) above 1992 levels by 2030, and 79-155cm (31-61in) by 2100. With tides higher than they have been in decades – and far higher than when this swampy, tropical corner of the US began to be drained and built on a century ago – many of south Florida’s drainage systems and seawalls are no longer enough. That means not only more flooding, but challenges for the infrastructure that residents depend on every day, from septic tanks to wells. “The consequences of sea level rise are going to occur way before the high tide reaches your doorstep,” says William Sweet, an oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Sea level rise is global. But due to a variety of factors – including, for this part of the Atlantic coast, a likely weakening of the Gulf Stream, itself potentially a result of the melting of Greenland’s ice caps – south Floridians are feeling the effects more than many others. While there has been a mean rise of a little more than 3mm per year worldwide since the 1990s, in the last decade, the NOAA Virginia Key tide gaugejust south of Miami Beach has measured a 9mm rise annually.

That may not sound like much. But as an average, it doesn’t tell the whole story of what residents see – including more extreme events like king tides (extremely high tides), which have been getting dramatically higher. What’s more, when you’re talking about places like Miami Beach – where, as chief resiliency officer Susanne Torriente jokes, the elevation ranges between “flat and flatter” – every millimetre counts. Most of Miami Beach’s built environment sits at an elevation of 60-120cm (2-6ft). And across the region, underground infrastructure – like aquifers or septic tanks – lies even closer to the water table……

Not only are sea levels rising, but the pace seems to be accelerating. That’s been noted before – but what it means for south Florida was only recently brought home in a University of Miami study. “After 2006, sea level rose faster than before – and much faster than the global rate,” says the lead author Shimon Wdowinski, who is now with Miami’s Florida International University. From 3mm per year from 1998 to 2005, the rise off Miami Beach tripled to that 9mm rate from 2006….

One graph compiled in 2015 by the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact, a non-partisan initiative that collates expertise and coordinates efforts across Broward, Miami-Dade, Monroe and Palm Beach counties, is especially revealing (see below). At the bottom is a dotted green line, which rises slowly. Before you get optimistic, the footnote is firm: “This scenario would require significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in order to be plausible and does not reflect current emissions trends.” More probable is the range in the middle, shaded blue, which shows that a 6-10in (15-25cm) rise above 1992 levels is likely by 2030. At the top, the orange line is more severe still, going off the chart – to 81 inches (206cm) – by the end of the century.

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170403-miamis-fight-against-sea-level-rise

#

Rebuttal from Paul Homeward:

The article continues to ramble on in similar vein.

But where are the real facts , and why has the BBC omitted them?

The BBC mentions the tide gauge at Virginia Key, just outside Miami.

We can see that the long term rate of sea level rise has been 2.92mm/yr, and that the rate of rise has been accelerating in recent decades:

https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/sltrends/sltrends_station.shtml?id=8723214

However, the data at Virginia only goes back to 1931. There is a much longer record going back to 1897 at Fernandina Beach, just up the Florida coast, which tells a completely different story:

https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/sltrends/sltrends_station.shtml?id=8720030

The overall rate of rise is a much less scary 2.15mm/yr, and more significantly the rate of rise now is no higher than it was in the first half of the 20thC, putting paid to the exponential rise in sea level quoted in the BBC report.

If we focus on the most recent 50-yr trends, we see that Virginia is running at 3.52mm/yr, but Fernandina is lower at 2.77mm. Clearly this difference has nothing whatsoever to do with climate change, and everything to do with local factors, most likely caused by water extraction.

And the story does not end there. Virtually the whole of the US East Coast is subsiding because of long term geological processes. The main one is the collapse of the forebulge of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Retreat of the ice sheet since the end of the ice age means that land under it is still springing back up. However, as that happens, land on the periphery, such as the Atlantic coast, is tilting downwards.

The rate of subsidence is highest further north, but on the Florida coast it is in the order of 0.4mm/yr.

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2016GL068015

What this means is that whereas the current relative rate of sea level rise (RSL) at Fernandina is 2.77mm/yr, subsidence accounts for about 0.4mm of this. Therefore the absolute sea level rise (ASL) is 2.37mm.

At Virginia Key, the combination of geological and local subsidence account for approximately 1.1mm/yr, nearly a third of the reported rise.

There is no evidence at all that Florida will see 81 inches of sea level rise by 2100, as hysterically reported. Based on current trends, a figure of 8 inches is more likely.

Miami has managed perfectly well with that amount of sea level rise in the past century, and I am sure they will continue to do so.

But that does not suit the BBC’s narrative, does it?