By Physicist Dr. Ralph B. Alexander

The popular but mistaken belief that today’s weather extremes are more common and more intense because of climate change is becoming deeply embedded in the public consciousness, thanks to a steady drumbeat of articles in the mainstream media and pronouncements by luminaries such as President Biden in the U.S., Pope Francis and the UN Secretary-General.

But the belief is wrong and more a perception than reality. An abundance of scientific evidence demonstrates that the frequency and severity of floods, droughts, hurricanes, tornadoes, heat waves and wildfires are not increasing, and may even be declining in some cases. That so many people think otherwise reflects an ignorance of, or an unwillingness to look at, our past climate. Collective memories of extreme weather are short-lived.

In this and subsequent posts, I’ll present examples of extreme weather over the past century or so that matched or exceeded anything we’re experiencing in the present-day world. I’ll start with hurricanes.

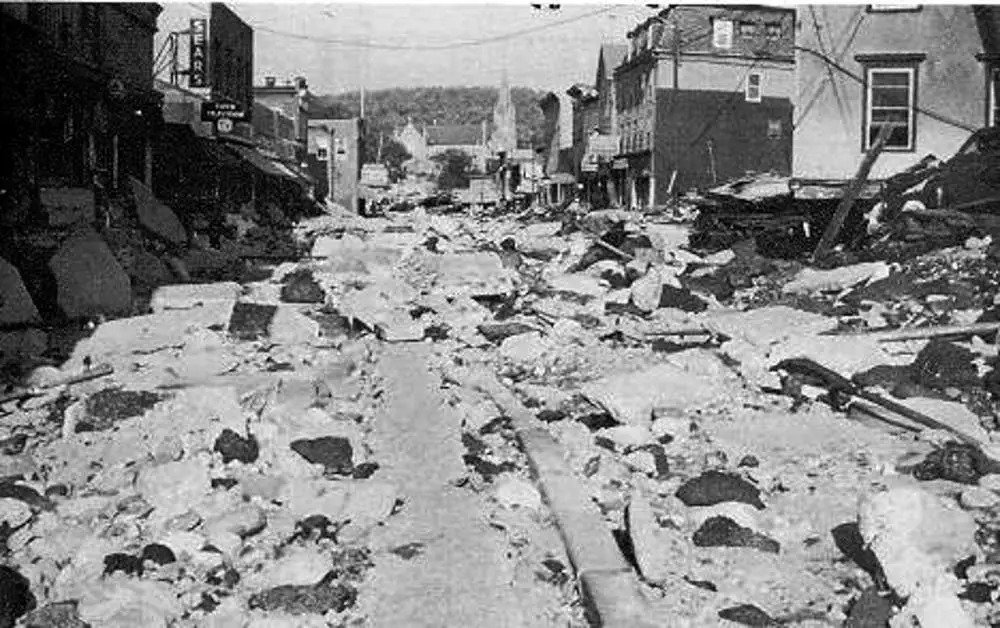

The deadliest U.S. hurricane in recorded history struck Galveston, Texas in 1900, killing an estimated 8,000 to 12,000 people. Lacking a protective seawall built later, the thriving port was completely flattened (photo on right) by winds of 225 km per hour (140 mph) and a storm surge exceeding 4.6 meters (15 feet). With almost no automobiles, the hapless populace could flee only on foot or by horse and buggy. Reported the Nevada Daily Mail at the time:

Residents [were] crushed to death in crumbling buildings or drowned in the angry waters.

Hurricanes have been a fact of life for Americans in and around the Gulf of Mexico since Galveston and before. The death toll has come down over time with improvements in planning and engineering to safeguard structures, and the development of early warning systems to allow evacuation of threatened communities.

Nevertheless, the frequency of North Atlantic hurricanes has been essentially unchanged since 1851, as seen in the following figure. The apparent heightened hurricane activity over the last 20 years, particularly in 2005 and 2020, simply reflects improvements in observational capabilities since 1970 and is unlikely to be a true climate trend, say a team of hurricane experts.

As you can see, the incidence of major North Atlantic hurricanes in recent decades is no higher than that in the 1950s and 1960s. Ironically, the earth was actually cooling during that period, unlike today.

Of notable hurricanes during the active 1950s and 1960s, the deadliest was 1963’s Hurricane Flora that cost nearly as many lives as the Galveston Hurricane. Flora didn’t strike the U.S. but made successive landfalls in Tobago, Haiti and Cuba (path shown in photo on left), reaching peak wind speeds of 320 km per hour (200 mph). In Haiti a record 1,450 mm (57 inches) of rain fell – comparable to what Hurricane Harvey dumped on Houston in 2017 – resulting in landslides which buried whole towns and destroyed crops. Even heavier rain, up to 2,550 mm (100 inches), devastated Cuba and 50,000 people were evacuated from the island, according to the Sydney Morning Herald.

Hurricane Diane in 1955 walloped the North Carolina coast, then moved north through Virginia and Pennsylvania before ending its life as a tropical storm off the coast of New England. Although its winds had dropped from 190 km per hour (120 mph) to less than 55 km per hour (35 mph) by then, it spawned rainfall of 50 cm (20 inches) over a two-day period there, causing massive flooding and dam failures (photo to right). An estimated total of 200 people died. In North Carolina, Diane was but one of three hurricanes that struck the coast in just two successive months that year.

In 1960, Hurricane Donna moved through Florida with peak wind speeds of 285 km per hour (175 mph) after pummeling the Bahamas and Puerto Rico. A storm surge of up to 4 meters (13 feet) combined with heavy rainfall caused extensive flooding all across the peninsula (photo on left). On leaving Florida, Donna struck North Carolina, still as a Category 3 hurricane (top wind speed 180 km per hour or 110 mph), and finally Long Island and New England. NOAA (the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) calls Donna “one of the all-time great hurricanes.”

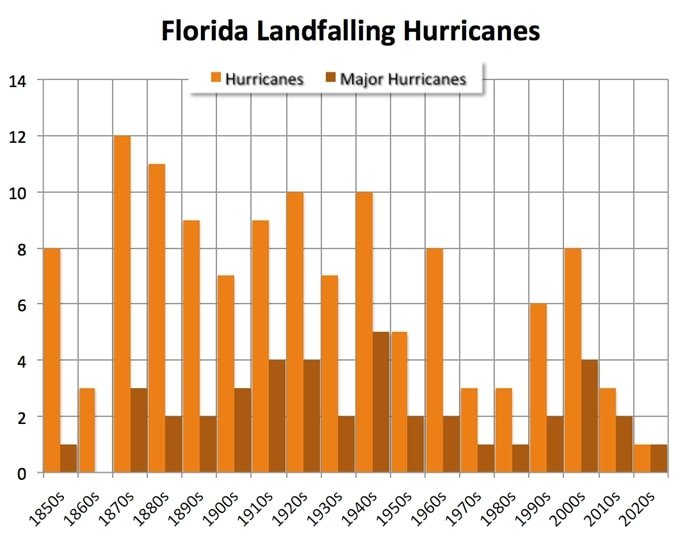

Florida has been a favorite target of hurricanes for more than a century. The next figure depicts the frequency by decade of all Florida landfalling hurricanes and major hurricanes (Category 3, 4 or 5) since the 1850s. While major Florida hurricanes show no trend over 170 years, the trend in hurricanes overall is downward – even in a warming world.

Hurricane Camille in 1969 first made landfall in Cuba, leaving 20,000 people homeless. It then picked up speed, smashing into Mississippi as a Category 5 hurricane with wind speeds of approximately 300 km per hour (185 mph); the exact speed is unknown because the hurricane’s impact destroyed all measuring instruments. Camille generated waves in the Gulf of Mexico over 21 meters (70 feet) high, beaching two ships (photo on right), and caused the Mississippi River to flow backwards. A total of 257 people lost their lives, the Montreal Gazette reporting that workers found:

a ton of bodies … in trees, under roofs, in bushes, everywhere.

These are just a handful of hurricanes from our past, all as massive and deadly as last year’s Category 5 Hurricane Ian which deluged Florida with a storm surge as high as Galveston’s and rainfall up to 685 mm (27 inches); 156 were killed. Hurricanes are not on the rise today.