Amazon forests really are cloud machines (and the climate models had no idea)

By Jo Nova

No wonder climate models can’t predict rainfall

” Until now, isoprene’s ability to form new [cloud seeding] particles has been considered negligible.”

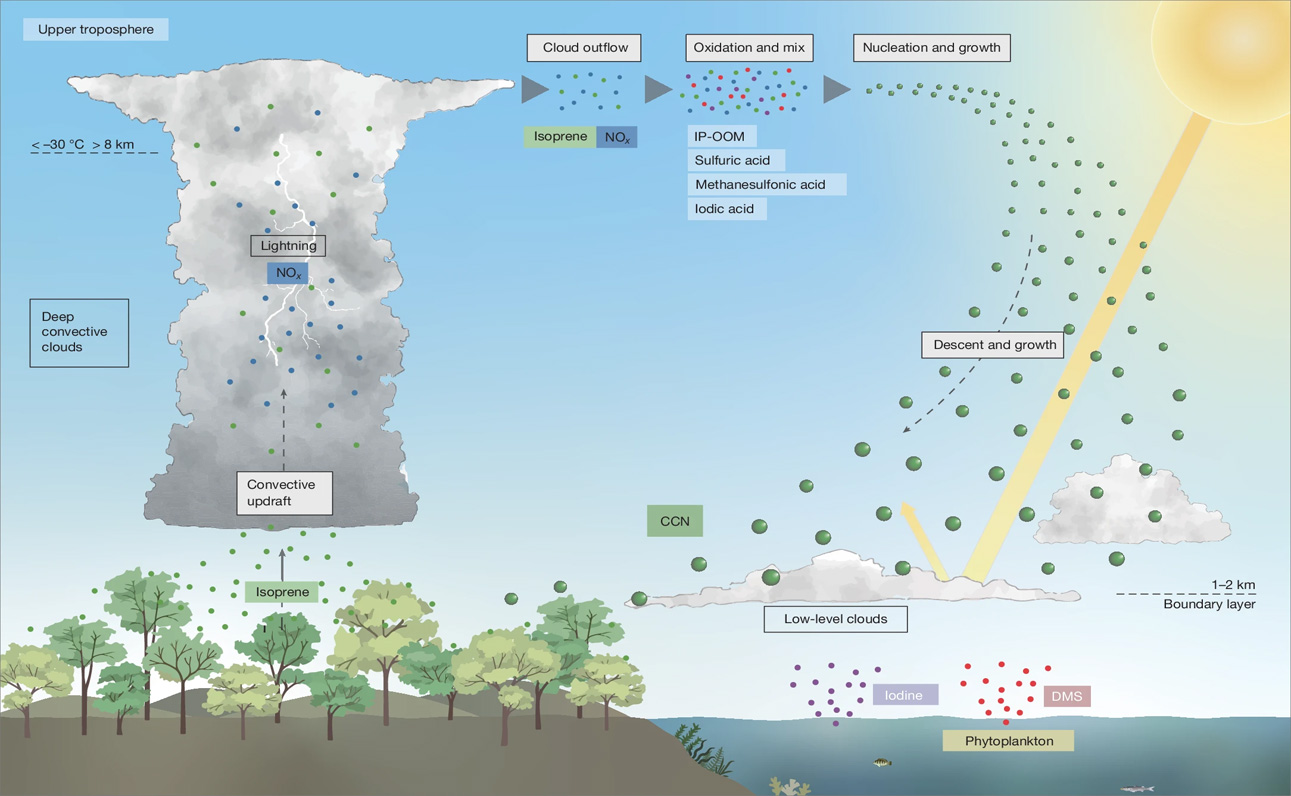

Broad leaf tees emit up to 600 million metric tons of isoprene each year, but no one thought it mattered much. For obvious reasons it is made near the ground, and it’s quite reactive and doesn’t last long. During daylight it’s destroyed within hours. So the experts didn’t think the isoprene could help seed clouds in the upper atmosphere. But there is still quite a lot of isoprene left in a rainforest at night, and tropical storms suck it up “like a vacuum cleaner” and pump it up and spray it out some 8 to 15 kilometers above the trees. Then powerful winds can take these molecules thousands of kilometers away.

When the sun rises, hydroxyl radicals start reacting with the isoprene again, but the reactions are quite different in the cold upper troposphere. And lightning may have left some nitrous oxides floating around too. This combination ends up making a lot of the seed particles that generate clouds in the tropics. It’s almost like the forests want to create more rain…

To put some perspective on this, isoprene is the most abundant non-methane hydrocarbon emitted into the atmosphere.

As Jasper Kirkby at CERN says — this is big:

Isoprene represents a vast source of biogenic particles in both the present-day and pre-industrial atmospheres that is currently missing in atmospheric chemistry and climate models.”

Until now, isoprene’s ability to form new particles has been considered negligible.

But climate models have also been estimating aerosols in the atmosphere for hundreds of years, and they didn’t realize trees made so much aerosol than they thought. This is so big, it may change the sacred “climate sensitivity” of the whole Earth:

“This new source of biogenic particles in the upper troposphere may impact estimates of Earth’s climate sensitivity, since it implies that more aerosol particles were produced in the pristine pre-industrial atmosphere than previously thought,” adds Kirkby. “However, until our findings have been evaluated in global climate models, it’s not possible to quantify the effect.”

Another possibility is that if forests of broadleaf trees turn out to be seriously helpful at seeding clouds, presumably that means the last few centuries of deforestation might have reduced cloud cover on Earth, which would have allowed much more sunlight in to heat the planet. If that’s true, it’s just one more climate forcing the modelers didn’t know about. It’s one more thing that warmed the planet which we blamed on carbon dioxide, but were wrong about. And it’s yet another feedback. More CO2 makes more forest grow, which may seed more clouds.

As usual, even though this study shows that climate models are missing yet another major factor, it’s always good news as they say: “The researchers, therefore, expect that their findings will contribute to improving climate models”. Hardly anyone says “The models were wrong, and the experts had no idea”.

The Amazon rainforest as a cloud machine: How thunderstorms and plant transpiration produce condensation nuclei

Who hasn’t enjoyed the aromatic scent in the air when walking through the woods on a summer’s day? Partly responsible for this typical smell are terpenes, a group of substances found in tree resins and essential oils. The primary and most abundant molecule is isoprene. Plants worldwide are estimated to release 500 to 600 million tons of isoprene into the surrounding atmosphere each year, accounting for about half the total emissions of gaseous organic compounds from plants.

Thunderstorms act like vacuum cleaners

… tropical thunderstorms … brew over the rainforest at night. They pull the isoprene up like a vacuum cleaner and transport it to an altitude of between 8 and 15 kilometers. As soon as the sun rises, hydroxyl radicals form, which react with the isoprene. But at the extremely low temperatures that prevail at these high altitudes, the rainforest molecules are transformed into compounds different from those near the ground. They bind with nitrogen oxides produced by lightning during the thunderstorm. Many of these molecules can then cluster to form aerosol particles of just a few nanometers. These particles, in turn, grow over time and then serve as condensation nuclei for water vapor—they thus play an important role in cloud formation in the tropics.

People at CERN were involved in testing the reactions at minus 30°C and minus 50°C

“High concentrations of aerosol particles have been observed high over the Amazon rainforest for the past twenty years, but their source has remained a puzzle until now,” says CLOUD spokesperson Jasper Kirkby. “Our latest study shows that the source is isoprene emitted by the rainforest and lofted in deep convective clouds to high altitudes, where it is oxidised to form highly condensable vapours.

In addition, the team found that isoprene oxidation products drive rapid growth of particles to sizes at which they can seed clouds and influence the climate – a behaviour that persists in the presence of nitrogen oxides produced by lightning at upper-tropospheric concentrations. After continued growth and descent to lower altitudes, these particles may provide a globally important source for seeding shallow continental and marine clouds, which influence Earth’s radiative balance (the amount of incoming solar radiation compared to outgoing longwave radiation).

This story reminds me of the big paper ten years ago Do forests create the wind that brings the rain?

“Rather than assuming that forests grow where the rain falls, it would be more a case of rain falling where forests grow. “

Forests can create their own rain,

Which climate models did not ascertain,

As gaseous molecules of isoprene,

Feed the rainforest cloud machine,

A hydrocarbon that is non-methane.

–Ruairi